Toolkit blueprint on citizen science

About

In a nutshell...

This blueprint describes a hands-on introduction to the world of pollinators science and related nature conservation practices. While it focuses on educational activities, all these include participatory elements, making the training very interactive and helping to link science to the daily lives of participants. The blueprint includes also workshop elements, in that towards the end, using the insights gained as well as their own knowledge, participants are invited to develop local monitoring and conservation actions for pollinators.

Purpose & objective

When it comes to pollinators, nature conservation depends on citizens in two important areas. First, the monitoring of pollinator species (their abundance and distribution) often depends on data collected by citizen scientists. Secondly, pollinators, especially in cities, can benefit greatly from even small actions, like managing private gardens in more pollinator-friendly manner. Responding to this double opportunity, this blueprint focuses very strongly on education about pollinators, but with an important twist. By referring to the existing knowledge and interests of participants, it connects pollinator conservation to their daily life and creates opportunities to shape nature conservation actions taking into consideration people's personal interests. The underlying idea is that before being able to contribute to nature conservation, citizens first need to find their personal way into the topic.

Format

Learning can be quite tedious if it uses long theoretical explanations, technical vocabulary and doesn't explain how the topic relates the lives of participants. That's why this blueprint makes use of artistic activities, participant inputs, conversations and outdoor time. When the participants are young, peer-to-peer learning format is preferable – though this approach can be used for many other groups. This event is hybrid, which creates flexibility in how the first, more educational and preparatory part of the event is organised, at the same time making the best of the face-to-face interactions.

Preparations

Recruitment

This is a good example of a process where an an open call can work very well, especially if done in collaboration with already established initiatives or well-known local institutions like schools, NGOs or municipalities. An open call in this case is sufficient (as opposed to recruiting a representative sample), as the focus is on small individual and collaborative actions – rather than large projects that influence all people living in a given area. Additionally, although this process can be implemented with a general public – including people with no prior interest in the topic – it can work best with those who have a pre-existing interest but want to deepen it further.

Team

In this process the most important member of the implementing team is an entomologist, who should have experience in nature communication or education more generally, to be able to share with citizens technical knowledge in an understandable manner but also to be able to integrate into their presentations the knowledge already held by citizens. It’s here that the peer-to-peer approach can be of great help. This might mean a young expert working with young participants but also simply having a person living in a city where the process takes place playing a key role in facilitation or presentation of knowledge. This creates a more relaxed, casual atmosphere and diminishes the distance between participants and organisers.

Location

This process is about local action, with its scope ideally limited to a city – but even better could be a neighbourhood. The location of the in-person part of the event should be a place familiar to all the participants – like a neighbourhood park.

Partnerships

Ideally, this process is developed with local experts and organisations. This makes the topic more relatable and provides immediately examples about what can be done in a given place. An ideal partner is a local NGO that’s implementing a nature conservation project in a given location. This can additionally provide participants a direct way to get involved in pollinator conservation efforts and seek guidance from local experts – and vice versa, it allows the organisation to get to know the locals and get better rooted in the community. Local conservation organisations also usually have best materials for local species identification.

Event roll-out

Opening

The first part of the process takes place online. The Opening, in which the organiser explains the process and the way of working together – a netiquette – is very important here, as online environment might be less familiar to some people than the real-world. As this is a process focused on local engagement, as an icebreaker you can ask participants to point on a (digital) map their favourite spots in the neighbourhood or the city and then invite them to explain why, writing short notes on digital post-its. This might also be an opportunity to discuss what pollinators people have seen in these places and how friendly these places are for insects.

Opening: Find out who your participants are!

For a process that focuses a lot on learning new things, it’s helpful for the organiser to understand the level of participants’ knowledge to know where to start and to identify the different levels. You can do this through small, simple activities, starting easy and building up. The first and simplest can be developing a word cloud with the pollinators that participants know. As this is anonymous, participants don’t have to worry about making mistakes or seeming ignorant. Many different free online softwares can be sued for this, e.g., Slido or Mentimeter. Unfortunately, the facilitator only gets to know the general level of the group. At the second stage, the facilitator can show participants a series of pictures of animals and invite them to vote whether each one is a pollinator or not. This can be done either through online voting, using platforms mentioned before, or through a simple hand raise – which allows to notice those with more or less knowledge. As the answers appear, the expert uses the right and wrong answers to elaborate on the species – and invites the participants to share their stories and explanations, why they chose or not specific animals. If large differences in knowledge are present, there are several strategies that can be used: you can add extra introductory sessions for those with less knowledge and/or extra in-depth sessions for participants with more advanced knowledge backgrounds, split groups according to the level or even invite the more knowledgeable participants to become ‘helpers’ throughout the event.

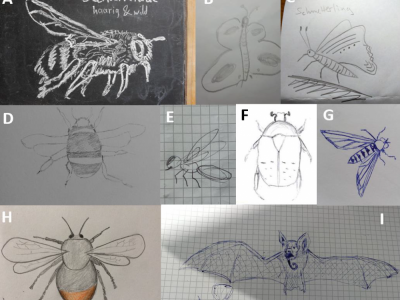

Noticing: Draw your favourite pollinators!

The next activity allows participants to take their creative side out and rest a moment from the screen. Recognising species is necessary for citizen science projects but can be tricky and the acquisition of sufficient knowledge might seem overwhelming at first. A good way to make it easier is to ground the skill in the already existing knowledge. Invite participants to take a piece of paper and a pencil and draw their favourite pollinator. Give participants about five to ten minutes time – these don’t need to be Mona Lisas. When done, invite them to take a picture of what they drew – they can do this with computer camera or with their phone and send the picture to an email or phone account set up for the project. Upload the pictures to a digital whiteboard as they come. If you do this anonymously, participants will not feel uncomfortable about comparing their drawing skills. Then proceed to analysing the drawings, pointing out the features visible in drawings which can be helpful in telling one species or group from another. This way participants recognise they already know much that can help them in recognising different species and groups. This activity is important as in the enormous diversity of pollinators it is sometimes difficult to tell one insect from another. Worryingly, taxonomists with a good knowledge of pollinators are themselves endangered species – much like many objects of their study – given the continuous drop in the number of experts and their high average age. Spreading the knowledge of – and interest in – the ability to recognise different pollinator species is thus very important. Especially among the younger audiences this might motivate later career decisions.

Noticing/Mapping?: Discuss the threats to pollinators!

After this introduction to pollinators, the event moves towards exploring different aspects of pollinators’ life. Invite participants to come up with as many threats to pollinators as they can think of, jotting them down on digital post-its. If needed, give participants a few minutes to do a search on the internet. After this quick brainstorming round, ‘clean’ the results by removing repetitions, meanwhile asking participants to group the proposals. When this is done, invite participants to a round of breakout room work, in smaller groups, where they can together reflect on two questions: What are the local examples of the threats they know of? Which of the threats to pollinators are also threats to them, personally, or to people in general? This activity makes the threats to pollinators both concrete, through local examples, and relatable, through identification with the problems they face. If you have time to go into depth, this can also be a good time to delve deeper into the reasons behind the threats to pollinators, through either the Iceberg Model or the Problems Tree. At the same time, as this activity focuses on problems, it might easily provoke a sense of despair and being overwhelmed. Hence, it’s a good idea to counterbalance it with an exercise that focuses on caring and protection of pollinators.

Noticing: Take a look where they live!

One such activity can be a closer look at insects’ needs and habitats through an investigation of a popular intervention in support of pollinators – an insect hotel. To make this activity most relatable to participants, ask them to do a small homework and bring with them photos of insect hotels they found in their neighbourhood. Then use a digital whiteboard and marking tools to dissect the hotels: What are the purposes of the different features? Which pollinators do they support? Which features are useful and which not? Where should an insect hotel be placed? Why? For instance, by pointing out the holes drilled in wood and how they are filled with dried mud, you can discuss the need for water in the vicinity. To move to a discussion of wider habitats, use a listening exercise. Ask participants to close their eyes and listen to a soundtrack composed of sounds from different pollinator habitats. Which sounds can they distinguish? What habitats they refer to and what needs do they fulfil? Apart from being a relaxing moment, this exercise also allows to connect to habitats in a new way.

Taking care for your hive: Listen to some music!

If you use for this exercise a soundtrack that develops into a musical piece, like it was done in the pilot project, this activity can become also a transition point to speaking about individual hobbies, passions and ways that participants use the places that are also pollinator habitats. Using the sounds of nature to create music is here just an example of many creative ways we can engage with the natural environments, that can put us in close contact with pollinators. This becomes a relaxed conversation to close the online part of the event, complementary to the opening conversation about participants’ favourite places.

Noticing: Explore a case study!

The in-person part of the workshop begins with a meeting with a local organisation, e.g. an environmental NGO, and their presentation of a project they are carrying out in the area. This can be a wildflower area, a nature trail, a habitat restoration project – but also many other things. This can help participants understand better how the general information about pollinators applies in the specific context. And thanks to the prior introduction to many of these topics, participants are in a better position to ask questions, thus exploring their own interest in the topic.

Noticing: Recall all you spoke about in the wild!

After this introduction, together with the local organisation representative take participants on a guided tour through the area, which will rediscover in practice the things that were previously discussed more in theory, like species recognition, habitats and pollinator needs, and threats. Before setting out, participants should be instructed on the use of tools like insect nets and glasses, which then they can try using in practice. The purpose of this activity is not just – and not even mainly – to teach the use of tools employed in insect monitoring, but rather to give an opportunity for closer contact with pollinators, as this tends to make the topic more concrete, meaningful.

In order to create something together, you can also instruct participants in the use of one of the citizen science apps, like Inaturalist, and invite participants to record their observations. This might require some time, as the use of such platforms is not always intuitive.

Co-design

Having learnt about pollinators and their decline, and following the discussions about the connections between them and individual lives of participants, this part of the event creates space for participants to reflect on the ways they could get involved in supporting pollinators. While a facilitated conversation can bring out general ideas, an activity like Outcasting can help make the plans more concrete. You can organise Outcasting exercise around participants' hobbies, inviting them to make groups of max 5 persons based on their shared interests. Alternatively, you can start with favourite places, thus linking back to the initial icebreaker activity. As an inspiration for seeking activities that can help pollinators, you can use this practical guidance for citizens on pollinator conservation. It will be most important that participants reflect on how such activities could best fit in their lives, so that they have the greatest chance to be successful. This is why the earlier parts of the event focused on helping participants find their own way of connecting to the topic. The participants could also bring their own understanding of the area and its needs to identify which actions could be helpful for pollinators – and perhaps at the same time also for human inhabitants.

Closing

To close the event, invite participants to share the ideas they have developed. A good idea is also to leave space for informal conversations between the participants and with the representatives of the local project. Through this ‘networking’ participants have an opportunity to join together to work on some project they particularly liked.

Credits

This blueprint is based on a series of workshops, mostly with younger audiences, conducted in Germany, Slovenia and Spain by Gerrit Öhm in 2020. The main purpose of the workshops was to use interactive activities to introduce young people to citizen science - especially in the context of diminishing numbers of taxonomy experts – and help them make the first steps towards involvement with nature conservation. Here we use many of the activities tested in those pilots and the overall structure, while putting more focus on participatory elements.

All photographs © Gerrit Öhm.